A UK-based cyberlaw blog by Lilian Edwards. Specialising in online privacy and security law, cybercrime, online intermediary law (including eBay and Google law), e-commerce, digital property, filesharing and whatever captures my eye:-) Based at The Law School of Strathclyde University . From January 2011, I will be Professor of E-Governance at Strathclyde University, and my email address will be lilian.edwards@strath.ac.uk .

Sunday, December 12, 2010

Wikileaks drips on: some responses

The main thrust of the point I was making is that settling a dispute of major public consequence by covert and non-legitimate bully boy tactics - covert pressure on hosts, payment services and DNS servers, plus DDOS attacks on Wikileaks hosts from the US-sympathising side - and anonymous DDOS attacks on sites like Amazon, Mastercard and Assange's alleged rape victims' lawyer's site from the Wikileaks-sympathising side - are BOTH the wrong thing to do. The point of a civilised society is suposed to be that disputes are settled by transparent legitimate and democratic, judicial or political processes. This has not been a particularly popular point with almost anybody, but it seems to me that it may indeed be naive (as some commenters have accused), but it is also, I stil think, both correct and needing saying, in the current frenzy around the First Great Infowar etc (it's 1996 all over again, yet again..).

One commenter asks not entirely unreasonably why it is justified for Amazon to take down content without going to court but "Vigilanteism" if the forces of Anonymous take down content extra judicially by DDOS attacks. The confusion here is in the word "justified". Amazon are justified, I argue, because since they host the content, they could be held legally liable for it (on a variety of grounds) if they do not take down having been given notice. That could lead to damages against them, injunctions blocking their site to customers (at their busiest time of the year) or even a prison sentence for their CEO . As a (liberal-sympathisng) friend in industry said to me, that last does tend to focus the mind. To state the bleeding obvious, Anonymous by contrast are not liable for the content they bring down.

But that meant I was saying Amazon were justified in a risk-management sense, and a legal sense, not an ethical sense. Was it Amazon's highest ethical duty to defend freedom of speech or to be responsible to their shareholders and their employees? That's a harder question. Many used to feel companies had no ethical duties at all, though that is gone in an era of corporate social responsibility (though this is still rarely if ever a legal obligation). Amazon's role is perhaps confused because they are best known as a consumer site selling books ie complicit with freedom of expression. Would we feel as aggrieved if Wikileaks had gone to a cloud host known only for B2B hosting? Perhaps, but what reason would there then be for expecting a host to behave like a newspaper?

What this leads us to as many, many commentators have pointed out is a renewed understanding that freedom of speech online is worryingly dependent on the good intentions of intermediaries whose core values and business model is not based on journalistic ethics, as was true for traditional news outlets in the offine age. This is hardly news: it has been making headines since at least 1996 when a Bavarian court convicted the CEO of Compuserve for distributing Usenet newsgroups to Europe, some of which happened to contain pornographic files. That incident among many others, lead to rules restricting the liability of hosts and intermediaries, in both the EU and US, which did quite well till round the early 2000s but are now struggling (not least because of pressure from both the copyright and the chld safety lobbies for less, not more, immunity). Not uncoincidentally, these rules are now being actively reviewed by among others, the EU, the OECD and WIPO. The really interesting question now will be what effect Wikileaks as a case study has on those debates.

Wednesday, December 01, 2010

Veni Vidi Wikileaks

This is interesting in all kinds of ways.

First, the initial move to Amazon was a clever one. In the old days, a concerted and continuing DDOS attack on a small site might have seen them off - nowadays there are plenty of commercial reasonably priced or free cloud hosts. So cloud computing can be seen as a bulwark for freedom of speech - vive les nuages!

Second, though of course, what strokes your back can also bite it, and here we have Amazon suddenly coming over shy. This appears to be entirely the sensible legal thing for them to do and anyone accusing them of bad behaviour should be accused right back of utter naivete. Amazon are now on notice from the government of hosting material which breached US national security and so would according to the US Espionage Act as quoted in the Guardian piece, fairly clearly have been at risk of guilt as a person who "knowingly receives and transmits protected national security information" if they had not taken down. (Though see a contrary view here.)

While Assange as an Australian not a US citizen, and a journalist (of sorts) might have had defences against the charges quoted also ( as canvassed in the Grauniad piece) Amazon, interestingly, would, it seems, not. They are American and by definition for other useful purposes (eg CDA s 230 (c) - see below and ye ancient Prodigy case) , not the sort of publisher who gets First Amendment protections. And Amazon has its CEO and its major assets in the US, also unlike Assange. I think that makes take down for Amazon a no-brainer. (And also interestingly, CDA s 230(c) which normally gives hosts complete immunity in matters of liability which might affect press freedom (such as defamation by parties hosted) does not apply to federal criminal liability.)

But as Simon B also pointed out, there are lots of other cloud suppliers , lots in Europe even. What if Wikileaks packs and moves again? Would any non US`host be committing a crime? That would depend on the local laws: but certainly it would be hard to see if the US Espionage Act could apply, or at any rate what effective sanctions could be taken against them if a US court ruled a foreign host service was guilty of a US crime.

Which leaves anyone wanting to stop access to Wikileaks, as Technollama already canvassed, the options of, basically, blocking and (illegal)DDOS (seperating the existence of the Wikileaks site from any action against Assange as an individual). Let's concentrate, as lawyers, on the former.

Could or would the UK block Wikileaks if the US`asked?

Well there is an infrastructure in place for exactly such. It is the IWF blacklist of URLs which almost all UK ISPs are instructed to block, without need for court order or warrant - and which is encrypted as it goes out, so no one in public (or in Parliament?) would need to know. This is one of the reasons I get so worked up about the current IWF when people are asking me if I won't think of the children.

There is also the possibility, as we saw just last week, of pressure being exerted not on ISPs but on the people who run domain name servers and the registrars that keep domain names valid. Andres G suggests that the US might exert pressure on ICANN to take down wikileaks.org for example. Wikileaks doesn't need a UK domain name to make itself known to the world, but interestingly only last week we also saw a suggestion from SOCA (not very well reported) that they should have powers effectively to force Nominet, the UK registry, to close down UK domain names being used for criminal purposes. Note though if you follow the link that that power could only be used if the doman was breaking a UK criminal law.

But there is a really simply non controversial way to allow UK courts the power to block Wikileaks. Or there may be soon.

Section 18 of the Digital Economy Act 2010 - remember that? - allows for regulations to be made for "the granting by a court of a blocking injunction in respect of a location on the internet which the court is satisfied has been, is being or is likely to be used for or in connection with an activity that infringes copyright."

Section 18, at present, needs a review and regulations to be made before it can come into force. This may in the new political climate perhaps never happen - who knows. But what if that had been seen to?

Wikileaks documents are almost all copyright of someone , like the US government, and are being used ie copied (bien sur) without permission. Hence almost certainly, a s18 fully realised could be used to block the Wikileaks site.Of course there is some possibility from the case of Ashcroft v Telegraph Group [2001] EWCA Civ 1142`that a public interest/freedom of expression defense to copyright infringement might be plead - but this is far less developed than it is in libel and even there it is not something people much want to rely on.

So there you go : copyright, the answer to everything, even Julian Assange :-)

Oh and PS - oddly enough the US legislature is currently considering a bill, COICA, which would also allow them to block the domain name of sites accused of encouraging copyright infringement. Handy, eh? (Though on this one point, the UK DEA s 18 is even less restrictive than COICA, which requires the site to be blocked to be "offering goods and services" in violation of copyright law - which is not even to a lawyer a description that sounds very much like Wikileaks.)

EDIT: Commenters have pointed out that official government documents in the US, unlike in the UK do not attract copyright. Howver the principle stands firm: embarrassing UK docs leaked by Wikileaks certainly would be prone to attack on copyright grounds, including DEA s 18, and it is quite possible some of the current Wikileaks documents could quote extensively from material copyright to individuals (and Wikileaks prior to the current batch of cables almost certainly contain copyright material).

Interestingly Amazon did in fact, subsequent to this piece, claim they removed Wikileaks from their service, not because of US pressure, but on grounds of breach of terms of service : see the Guardian 3 December 2010

"for example, our terms of service state that 'you represent and warrant that you own or otherwise control all of the rights to the content… that use of the content you supply does not violate this policy and will not cause injury to any person or entity.' It's clear that WikiLeaks doesn't own or otherwise control all the rights to this classified content. Further, it is not credible that the extraordinary volume of 250,000 classified documents that WikiLeaks is publishing could have been carefully redacted in such a way as to ensure that they weren't putting innocent people in jeopardy. Human rights organisations have in fact written to WikiLeaks asking them to exercise caution and not release the names or identities of human rights defenders who might be persecuted by their governments."

The copyright defense is alive and well :-)

Job opportunity

As advisory board meber of ORG, I was asked to help spread the word about a new job opportunity with the Open Rights Group, where for the first time we're looking to hire someone with some kind of legal background. If you’re a London-based law student, trainee in waiting, or other legal type with an interest in IT and/or IP law, then you may want to check the following new job at ORG:

The Open Rights Group, a fast-growing digital rights campaigning organisation, are looking for a Copyright Campaigner to take our campaigning on this fast moving area to a new level.

You will work as a full time campaigner to reform copyright and protect individuals from inappropriate enforcement laws like ‘three strikes’. We’re after someone with a passion for this area who has a proven ability to organise and deliver effective campaigns.

We are looking for someone with excellent communication skills, good organisational and planning skills, who works well in a team environment and is able to prioritise their own work without depending on line management. You will be able to demonstrate commitment to our digital rights.

The jobs is full time for one year, with the possibility of extension to a second year. Salary: £30,000.

Welcome back to me

So to kick off, a reprise of my annual not-very-serious predictions for next year, from the SCL journal site (where many more such can be found.)

"1. France will pass a law forbidding French companies from using cloud computing companies based anywhere other than France. Germany will ban cloud computing as unfair competition with German companies. Ireland will consider putting its banking in the cloud, but realise there's no point as they have no money left.

2. A Google off-shore water-cooled server farm will be kidnapped by Somali pirates, towed to international waters, repurposed as encrypted BitTorrent client and take over 95% of the world's traffic in infringing file-sharing (with substantial advertising revenue, of course) (thanks to Chris Millard for this one). (Meanwhile the Irish will attempt to nationalise all the Google servers they still host on shore to pay for bailing out the banks.)

3. TalkTalk will lose their judicial review case against the Digital Economy Act, but the coalition will find some very good reason to delay bringing in the Initial Obligations code, and the technical measures stage will quietly wither on the vine, as rights-holders realise it will cost them more to pay for it than they will gain in royalties.

4. 120% of people of the world including unborn children, all except my mother, will join Facebook. Mark Zuckerberg will buy Ireland and turn it into a Farmville theme park, with extra potatoes.

5. 4chan allied with Anonymous will hack Prince William's e-mail inbox on the eve of the Royal Wedding, revealing he is secretly in love with an older, plainer and less marriageable woman than Kate Middleton (possibly Irish), and also illicitly downloads Lady Gaga songs. In retaliation, the coalition passes emergency legislation imposing life imprisonment as the maximum penalty for DDOS attacks, and repeals the Digital Economy Act."

Lawrence Eastham kindly says that he can see at least 2 of these coming true.I imagine one of those is no 3, but which do you think the other was, dear readers?

As a final amuse-bouche beforeI return to Proper Things, have a picture of someone skiiing to the local shops this morning. yes. Not Seefeld. Sheffield. Merry Xmas!

Sunday, October 03, 2010

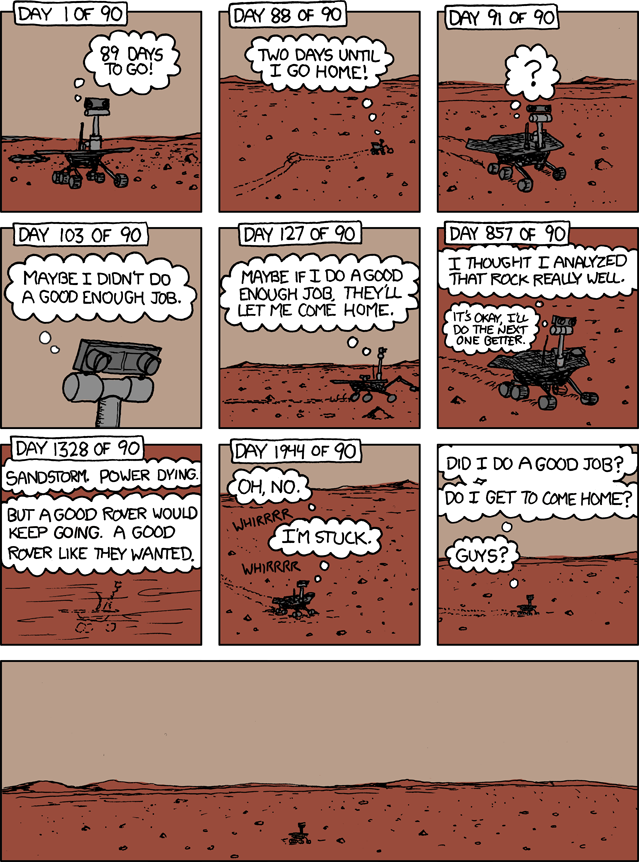

OK I lied: this is the last robot post..

I was trying to remember for the last five days, the saddest most anthromoporphic [NOTE: canomorphic??] piece of robot culture I'd ever seen...

Why We Shouldn'T Date Robots

Futurama - Don't date robots from John Pope on Vimeo.

Friday, October 01, 2010

Edwards' Three Laws for Roboticists

A while back I blogged about how delighted I was to have been invited by the EPSRC to a retreat to discuss robot ethics, along with a dozen and half or so other experts drawn not just from robotics and AI itself but also from industry, the arts, media and cultural studies, performance, journalism, ethics, philosophy, psychology - and er, law (ie , moi.)

The retreat was this week, and two and a half days later, Pangloss is reeling with exhaustion, information overload, cognitive frenzy and sugar rush :-) It is clear this is an immensely fertile field of endeavour, with huge amounts to offer society. But it is also clear that society (not everywhere - cf Japan - but in the UK and US at least - and not everyone - some kids adore robots) has an inherited cultural fear of the runaway killer robot (Skynet, Terminator, Frankenstein yadda yadda), and needs a lot of reassurance about the worth and safety of robots in real life, if we are to avoid the kind of moral panics and backlashes we have seen around everything from GM crops to MMR vaccinations to stem cell surgery. (Note I have NOT here used a picture of either Arnie or Maria from Metropolis, those twin peaks of fear and deception.)

Why do we need robots at all if we're that scared of them, then? Well, robots are already being used to perform difficult dirty and dangerous tasks that humans do not want to do, don't do well or could not do because it would cause them damage, eg in polluted or lethal environments such as space or undersea. (What if the Chilean miners had been robots?? They wouldn't now be asking for cigarettes and alcohol down a tube..) )

Robots are also being developed to give basic care in home and care environments, such as providing limited companionship and doing menial tasks for the sick or the housebound or the mentally fragile. We may say (as Pangloss did initially) that we would rather these tasks be performed by human beings as part of a decent welfare society : but with most the developed world facing lower birth rates and a predominantly aging population, combined with a crippling economic recession, robots may be the best way to assure our vulnerable a bearable quality of life. They may also give the vulnerable more autonomy than having to depend on another human being.

And of course the final extension of the care giving robot is the famous sexbot , which might provide a training experience for the scared or blessed contact for the disabled or unsightly - or might introduce a worrying objectification/commodification of sex, and sex partners, and an acceptance of the unaceptable like sexual rape and torture, into our society.

Finally and most controversially robots are to a very large extent being funded at the cutting edge by military money. This is good ,because robots in the frontline don't come back in body bags - one reason the US is investing extensively. But it is also bad, because if humans on the frontline don't die on one side, we may not stop and think twice before launching wars, which in the end will have collateral damge for out own people as well as risk imposing devastating casualties on human opposition from less developed countries. We have to be careful in some ways to avoid robots making war too "easy" (for the developed world side, not the developing of course - robots so far at least are damn expensive.)

Three key messages came over:

- Robots are not science fiction. They already exist in their millions and are ubiquitous in the developed world eg robot hoovers, industrial robots in car factories, care robots are being rolled out even in UK hospitals eg Birmingham. However we are at a tipping point because until now robots of any sophistication have mostly been segregated from humans eg in industrial zones. The movement of robots into home and domestic and care environments, sometimes interacting with the vulnerable, children and the elderly especially, brings with it a whole new layer of ethical issues.

- Robots are mostly not humanoid. Again science fiction brings with it a baggage of human like robots like Terminators, or even more controversially, sex robots or fembots as celebrated in Japanese popular culture and Buffy. In fact there is little reason why robots should be entirely humanoid , as it is damn difficult to do - although it may be very useful for them to mimic say a human arm, or eye, or to have mobility. One development we talked a lot about were military applications of "swarm" robots. These resemble a large number of insects far more than they do a human being. Other robots may simply not even resemble anything organic.

-But robots are still something different from ordinary "machines" or tools or software. First, they have a degree of mobility and/or autonomy. This implies a degree of sometimes threatening out of control-ness. Second, they mostly have capacity to learn and adapt. This has really interesting consequences for legal liability: is a manufacturer liable in negligence if it could not "reasonably foresee" what its robots might eventually do after a few months in the wild?

Third, and perhaps most interestingly, robots increasingly have the capacity to deceive the unwary (eg dementia patients) into believing they are truely alive, which may be unfortunate (would you give an infertile woman a robot baby which will never grow up? would you give a pedophile a sex robot that looked like a child to divert his anti social urges?). Connectedly, they may manipulate the emotions and alter behaviour in new ways: we are used to kids insisting on buying an entire new wardrobe for Barbie, but what about when they pay more attention to their robot dog (which needs nothing except plugged in occasionally) than their real one, so it starves to death?

All this brought us to a familiar place, of wondering if it might be a good start to consider rewriting Asimov's famous Three Laws of Robotics. But of course Asimov's laws are - surprise!! - science fiction. Robots cannot and in foreseeable future will not, be able to understand, act on, be forced to obey, and most importantly reason with, commands phrased in natural language. But - and this came to me lit up like a conceptual lightbulb dipped in Aristotle' imaginary bathtub - those who design robots - and indeed buy them and use them and operate them and modify them - DO understand law and natural language, and social ethics. Robots are not subjects of the law nor are they responsible agents in ethics ; but the people who make them and use them are. So it is laws for roboticists we need - not for robots. (My thanks to the wonderful Alan Winfield of UWE for that last bit.)

So here are my Three Laws for Roboticists, as scribbled frantically on the back of an envelope. To give context, we then worked on these rules as a group, particularly a small sub group including Alan Winfield, as mentioned above , and Joanna Bryson of University of Bath, who added two further rules relating to transparency and attribution (I could write about them but already too long!).

It seems possible that the EPSRC may promote a version of these rules, both in my more precise "legalese" form, and in a simpler, more public-communicative style, with commentary : not, obviously, as "laws" but simply as a vehicle to start discussion about robotics ethics , both in the science community and with the general public. It is an exciting thing for a technology lawyer to be involved in, to put it mildly :)

But all that is to come: for now I merely want to stress this is my preliminary version and all faults, solecisms and complete misunderstandings of the cultural discourse are mine, and not to be blamed on the EPSRC or any of the other fabulously erudite attendees. Comments welcome though :)

Edwards' Three Laws for Roboticists

1.Robots are multi-use tools. Robots should not be designed solely or primarily to kill, except in the interests of national security.

2 Humans are responsible for the actions of robots. Robots should be designed & operated as far as is practicable to comply with existing laws & fundamental rights and freedoms, including privacy.

3) Robots are products. As such they should be designed using processes which assure their safety and security (which does not exclude their having a reasonable capacity to safeguard their integrity).

My thanks again to all the participants for their knowledge and insight (and putting up with me talking so much), and in particular to Stephen Kemp of the EPSRC for organising and Vivienne Parry for facilitating the event.

Phew. Time for t'weekend, Pangloss signing off!

Tuesday, September 28, 2010

Location, Location, Geolocation..

Thursday, September 23, 2010

Google's Transparency Tool: some thoughts

Google has released a tool , to much media and legal interest, which allows the public to see what requests are made by governments for information about users and, in particular, what requests were made to "take down" or censor content altogether. We have therefore one of the first reliable indices of the extent of global government censorship of online content as laundered through private online intermediaries.

This for eg is the data currently disclosed, for the last 6 months, for the UK:

- Blogger

- 1 court orders to remove content

- 1 items requested to be removed

- Video

- 3 court orders to remove content

- 32 items requested to be removed

- Groups

- 1 court orders to remove content

- 1 items requested to be removed

- Web Search

- 8 court orders to remove content

- 144 items requested to be removed

- YouTube

- 6 court orders to remove content

- 29 non-court order requests to remove content

- 54 items requested to be removed

- Blogger

- 8 court orders to remove content

- 11 items requested to be removed

- Video

- 1 court orders to remove content

- 2 items requested to be removed

- Google Suggest

- 2 court orders to remove content

- 3 items requested to be removed

- Web Search

- 47 court orders to remove content

- 1 non-court order requests to remove content

- 1094 items requested to be removed

- Book Search

- 2 court orders to remove content

- 2 items requested to be removed

- YouTube

- 17 court orders to remove content

- 46 non-court order requests to remove content

- 295 items requested to be removed

- AdWords

- 1 court orders to remove content

- 1 items requested to be removed

- Blogger

- 8 court orders to remove content

- 45 items requested to be removed

- Geo (except Street View)

- 2 court orders to remove content

- 2 items requested to be removed

- Video

- 1 court orders to remove content

- 1 items requested to be removed

- Groups

- 7 court orders to remove content

- 394 items requested to be removed

- Web Search

- 30 court orders to remove content

- 2 non-court order requests to remove content

- 66 items requested to be removed

- YouTube

- 31 court orders to remove content

- 46 non-court order requests to remove content

- 169 items requested to be removed

There is an enormous wealth of data here to take in. I was asked to comment on it to the BBC at a time when I had not yet had a chance to examine it in any depth, so this is an attempt to give a slightly more reflective response. Not that I'm in any way reneguing on my first gut response: this is a tremendous step and a courageous one for Google to take and deserves applause. It should be a model for the field and as Danah Boyd and others have already said on Twitter, it raises serious questions of corporate social responsibility if Facebook, the various large ISPs, and other platforms do not now follow suit and provide some form of similar disclosure. If Google can do it, why not the rest?

Pangloss has some appreciation of the difficulty of this step for a service provider. Some years back I attempted to do a small scale survey of notice and take down practices in the UK only, asking data from a variety of hosts and ISPs, including large and small, household names and niche enterprises, major industry players and non profit organisations. It was, it became quickly clear, an impossible task to conduct on any methodologically sound research level. Though many managers, IT folk and sysadmins we spoke to were sympathetic to the need for public research onto private non transparent censorship, nearly all were constrained not to disclose details by "business imperatives", or had no such details to hand in any reliable or useful format, which often came to the same thing. (Keeping such data takes time and labour: why bother when there is only trouble arising from doing so? See below..)

The fact is the prevalent industry view is that there are only negative consequences for ISPs and hosts to be transparent in this area. If they do reveal that they do remove content (or block it) or give data about users, they are vilified by both users and press as censors or tools of the police state. They worry also about publicly taking on responsibility for those acts disclosed- editorial responsibility of a kind, which could involve all kinds of legal risk including tipping off, breach of contract and libel of the authors of content removed or blocked. It is a no win game. This is especially true around two areas : child pornography, where any attempt after notice to investigate a take down or block request may involve the host in presumptive liability for possession or distribution itself; and intercept and record requests in the UK under the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act 2000 where (inter alia) s 19 may make it a criminal offence to even disclose that the government has asked for certain kinds of interceptions of communications.

Now imagine these legal risks and uncertainties, coupled with the possibility of a PR disaster - coupled with potential heavy handed government pressure - multiplied by every legal jurisdiction for which Google has disclosed data. This gives you some idea of the act of faith being undertaken here.

Google of course have their own agendas here: they are not exactly saints. Good global PR this may accrue among the chattering (or twittering) classes will help them in their various current wars against inter alia the DP authorities of Europe over Google Street View, the Italian state over Google Video and the US content industry over YouTube. But it still remains true as they say that "greater transparency will give citizens insight into these kinds of actions taken by their governments".

Criticisms

The legal risks I talk about above also partly explain some of the failings of the tool so far, some of which have been cogently pointed out already by Chris Soghoian. Notably, it is not yet granular enough, something Google themselves have acknowledged. We have numbers for data requests made (ie information about Google users) , for takedown requests, and which services were affected (Blogger, YouTube etc). We have some idea that Google sometimes received a court order before disclosing or blocking, and sometimes didn't, but we do not know how often they gave in specifically to the latter - only that it is claimed such requests were granted only where Google's own abuse policies were breached eg on Blogger.

Crucially we do not know, for the UK say, if these requests were made under RIPA or the Communications Act s 127 or more generic policing & investigation powers or what. Or how many related to terror material or pro islamic websites, and how many to scam or spam sites or illegal pharma shops or adult porn sites, say. Or even to defamation (this is apparently responsible for a high number of the requests in Germany, according to the FAQ.) Defamation is an odd one here because it is a private law not a criminal matter in the UK at least (some states do have criminal defamation, but it is fairly rarely tried); but it leads to court orders to remove content and disclose IDs, and Google, slightly confusingly, say they count these court orders in with the "governmental" stats. (They don't however include court orders for take down of copyright material, since these almost all come from private parties - and pragmatically, would probably overwhelm the figures.)

(Another important point buried in the FAQ is that these figures don't include removals for child pornography since Google's systems don't distinguish here, they say, between requests received from government, and from private parties - so eg all the take downs and blockings ordered by the IWF in the UK are presumably not included. This also means that those already high figures for Brazilian government requests for take down on Orkut are actually in reality probably a lot higher (?) since Orkut is renowned as a haven for hosting child porn.)

Splitting up requests and takedowns by type of content is critical to understanding the validity of state action, and the more data we get in future on this will be good. Once requests and removals are divided up by type (and legitimate authority), we can also find out what percentage of take down requests in which category were acceded to, still without Google needing to disclose at the possibly dodgy level of individual requests. And also where acceded to with or without court order.

Global comparisons and free speech

Looking at the data on a global comparison basis will be a daunting but fascinating task for commentators for the future, especially as the data grows across time. It is noticeable even from just the 3 countries quoted above that it is really, really complicated to make simplistic comparisons. (This is why few if any commentators yesterday were being dragged into easy condemnations and quicky league table comparisons. )

For example, the UK government made a lot of user data requests (a helluva lot if correlated to population actually - the US has six times the population of the UK but made much less than 4 times as many requests; Germany is a quarter bigger than the UK by population and made c 50% less requests) . By that figure, the UK is the most interrogatory government in Europe.

But Germany by contrast made more requests for take down of content than the UK - and got 94% of its requests accepted, compared to 62% of the UK's such requests). What does this say about the claim to validity of the UK requests overall? Are our LEAs more willing to try it on than Germany's, or was their paperwork just more flawed?? Do we try to get more take down without court orders and Google thus tells us to bog off more? Do we actually censor less content than Germany, or just fail to ask for removal of lots of stuff via one efficient takedown message rather than in a trickle of little ones? Needs further citation, as they say.

Google do interestingly say in the useful FAQ that the number of global requests for removal of speech on "pure" political grounds was "small" . Of course one country's politics is another's law. So approximately 11% of the German removal requests related to pro-Nazi content or content advocating denial of the Holocaust, both of which are illegal under German law - but which would be seen as covered by free speech in say the US.

Non governmental disclosure and take down requests

Finally of course these figures say nothing about requests for removal of content or disclosure of identities made by private bodies (except in the odd case of defamation court orders, noted above) - notably perhaps requests made for take down on grounds of coopyright infringement. There will be a lot of these and it would really help to know more about that. As recent stories have shown, copyright can also be used to suppress free speech too, and not just by governments.

Finally finally..quis custodiet ipse Google?

...a reader on Twitter said to me, yes, it's great but why should we believe Google's figures? He has a point. Independent audit of these figures would help. But it is difficult to know without technical info from an insider (hello Trev!) how far this is technically possible given the need for this kind of information capture on such a huge scale to be automated. (At least if we had the categories of requests broken down by legal justification, we could conceivably check them against any official g9vernmental stats - so, eg, in the UK checking RIPA requests against the official figures?? - though I doubt those currently disclose enough detail and certainly not who the requests were made against? (A. Nope! surprise - see 2009 Interception of Communications Commizssioner's report, eg para 3.8.))

Friday, September 17, 2010

My IGF presentation

Monday, September 13, 2010

New Job!

More of that when it kicks off properly tomorrow, but for now Pangloss is delighted to announce that from 1 January 2011, she will be taking up a new post as Chair of E-Governance at Strathclyde University in Glasgow.

Although she is sad to say goodbye to Sheffield, this is not only a homecoming to Scotland but also something of a dream job: a "research leadership" John Anderson Chair where for the first three years at least, the job is dedicated to forging cross-university and external interdisciplinary links to build IT-related research at Strathclyde.

I will also be taking over, with existing colleagues, charge of Strathclyde's already world-leading LLM and distance learning programmes in IT and Telecoms law: watch this space as we plan to expand, rebrand and add new modules to these already well-known enterprises.

I will also be actively seeking to build a community of PhDs and postdocs in IT law-related areas and looking for interesting new collaborators to build up funded and sponsored research . If you are interested in any of this, do let me know! Themes especially relevant to Strathclyde are likely to include Human Rights and the Internet, Internet Governance, Cyber Crime and Cyber Security, and The Mobile and Next Generation Internet (eg the Semantic Web and Robotics).

See culture - see IT - see Strathclyde! where the future's miles better :-)

Thursday, August 19, 2010

Top Gear, Privacy and Identity

Fascinating story of the week is that Top Gear's famous pet racing driver, The Stig ("some say he is the bastard child of Sherlock Holmes and Thierry Henri") wants to break his contractual and confidential obligations of silence as to his true identity imposed by his (presumably lucrative) BBC contract, so that he can reveal his name and make big $$$ out of his autobiography, in the style of his fellow presenters Clarkson et al, all of whom have reportedly made millions out of parlaying their popularity from the show.

It's a cracker this, in a week when the headlines are already full of a half hint that the Con_Dem government are thinking of having a bash at Eady J's judge-made law on privacy, breach of confidence and press freedom. The general tone of the hints in press has been that the balance has shifted too far in favour of protecting celebrity privacy, and too far from allowing the press to make lots of money out of kiss and tell tittle tattle, sorry," fulfil their public investigative duties".

So we already have an extensive debate about how far celebrities should be able to preserve their privacy even where they live their lives to some extent in public; but till now we've rarely had a debate about whether the "right to respect for private life" (Art 8 of the ECHR, which founds the recent line of English cases on privacy and confidence) also covers the right to disclose as well as hide your secrets.

From one perspective, the right to assert your "nymic" identity seems clearly like something that should be an intrinsic part of private life. In more modern instruments than the ECHR, such as the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, a right to a name and an identity is explicit. In the ECHR, case law has extended the right to family life to something very similar, with numerous cases on the rigt to a name, to a state affiliation qand to an immigration or domicile status. These cases are complex and go both ways but the underlying notion that private life includes identity is one which most scholars would I think acknowledge.

But another way to look at it - and one I am sure the BBC lawyers are quite keen on - is that this was a simple commercial transaction where the Stig was paid for silence. Non disclosure agreements (contracts) or NDAs are of course ubiquitous. As with the general domain of privacy and personal data online, the question then becomes the more controversial one of how far should you be able to sign away your basic rights by contract. Adopting the language of restrictive covenants, it would be surely be unreasonable if The Stig was not allowed to use his own name in any walk of life, or with any employer. But is it reasonable that be be bound indefinitely by his consent even by the BBC? The question also arises of what remedy would be reasonable here if the BBC were say to seek an injunction to prevent any name-attached autobiography of The Stig being published. In libel law, , the common aphorism is that common law courts prefer not to grant allow prior restraint of speech on allegations of defamation, but to impose damages subsequent to publication if damage to reputation then ensued: "publish and be damned". In pure contract or confidence actions, such a bright line does not pertain. Should The Stig have the right to assert his name and pay the BBC if they suffer loss as a result? Or should he be stoppable by injunction as is possible in the ordinary law of breach of contract?

I'd love to see this go to court but I strongly suspect it'll settle .

Wednesday, August 18, 2010

IGF: upcoming

IGF Workshop on "The Role of Internet Intermediaries in Advancing Public Policy Objectives"

The goal of the Workshop is to discuss and identify lessons learned from experience to date of Internet intermediaries in helping to advance public policy objectives. The workshop will introduce the concept of “Internet intermediaries”, the categories of actors considered, their role, and the three ways in which intermediaries can take on a policy role: through responses to legal requirements; through their business practices; and through industry self-regulation. It will discuss the roles and responsibilities of Internet intermediaries for actions by users of their platforms, their nature and extent and the implications. The workshop is part of a stream of work being conducted by the OECD.

The workshop will take place on September 16 from 14.30 to 16.30, in Room 1.

Wednesday, August 11, 2010

Social networks, 2010 vn

As someone whose last book used the original,wonderful xkcd cartoon as its cover, it seems only right to bring you the updated version! (NB NOT by Randall Munroe, though glad to see they acknowledge him.)

ps but shouldn't that be "sunken island of Google Buzz?"

Do robots need laws? : a summer post:)

I can so use this for the EPSRC Robotics Retreat I am going to in September!! (via io9 with thanks to Simon Bradshaw)

Another slightly more legal bit of robotics that's been doing the rounds, is this robots.txt file from the last.fm site. Robots.txt for the non techies are small text files which give instructions to software agents or bots as to what they are allowed to do on the site. Most typically, they do or don't tell Google and other search engines whether they are allowed to make copies of the site or not ("spider" it). No prize at all for the first person to realise what famous laws the last three lines are implementing:-)

User-Agent: *

Disallow: /music?

Disallow: /widgets/radio?

Disallow: /show_ads.php

Disallow: /affiliate/

Disallow: /affiliate_redirect.php

Disallow: /affiliate_sendto.php

Disallow: /affiliatelink.php

Disallow: /campaignlink.php

Disallow: /delivery.php

Disallow: /music/+noredirect/

Disallow: /harming/humans

Disallow: /ignoring/human/orders

Disallow: /harm/to/self

Allow: /

This all raises a serious underlying question (sorry) which is, how should the law regulate robots? We already have a surprising number of them. Of course it depends what you call a robot: Wikipedia defines them as "an automatically guided machine which is able to do tasks on its own, almost always due to electronically-programmed instructions".

That's pretty wide. It could mean the software agents or bots that as discussed above, spider the web, make orders on auction sites like eBay, collect data for marketing and malware purposes, learn stuff about the market, etc - in which case we are already awash with them.

Do we mean humanoid robots? We are of course, getting there too - see eg the world's leading current example, Honda's ASIMO, which might one day really become the faithful, affordable, un-needy helpmate of our 1950's Campbellian dreams . (Although what happens to the unemployment figures then?? I guess not that much of the market is blue collar labour anymore?) .But we also already live in a world of ubiquitous non humanoid robots - such as in the domestic sector, the fabulous Roomba vacuum cleaner, beloved of geeks (and cats); in industry, automated car assembly robots (as in the Picasso ads) ; and, of course, there are emergent military robots.

Only a few days ago, the news broke of the world's alleged first robot to feel emotions (although I am sure I heard of research protypes of this kind at Edinburgh University's robotics group years back.) Named Nao, the machine is programmed to mimic the emotional skills of a one-year-old child.

"When the robot is sad it hunches its shoulders forward and looks down. When it is happy, it raises its arms, looking for a hug.

The relationships Nao forms depend on how people react and treat it |

When frightened, it cowers and stays like that until it is soothed with gentle strokes on the head.The relationships Nao forms depend on how people react and treat, and on the amount of attention they show."

Robots of this kind could be care-giving companions not only for children, but perhaps also in the home or care homes for lonely geriatrics and long term invalids, whose isolation is often crippling. (Though again I Ludditely wonder if it wouldn't be cheaper just to buy them a cat.)

Where does the law come into this? There is of course the longstanding fear of the Killer Robot: a fear which Asimov's famous first law of robotics was of course designed to repel. (Smart bombs are of course another possibility which already, to some extent exist - oddly they don't seem to create the same degree of public distrust and terror, only philosophical musings in obscure B-movies.) But given the fact that general purpose ambulant humanoid artificially intelligent robots are still very much in the lab, only Japan seems so far to have even begun to think about creating rules securing the safety of "friendly AIs" in real life, and even there Google seems to show no further progress since draft guidelines were issued in 2007.But the real legal issues are likely to be more prosaic, at least in the short term. If robots do cause physical harm to humans (or, indeed, property) at the moment the problem seems more akin to one for the law of torts or maybe product liability than murder or manslaughter. We are a long away away yet from giving rights of legal personality to robots. So there may be questions like how "novel" does a robot have to be before there will be no product liability because of the state of the art defense? How much does a robot have to have a capacity to learn and determine its own behaviours before what it does is not reasonably foreseeable by its programmer?? Do we need rules of strict liability for robot behaviour by its "owners" - as Roman law did and Scots law still does for animals, depending on whether they are categorised as tame or wild? And should that liability fall on the designer of the software, the hardware, or the "keeper" ie the person who uses the robot for some useful task? Or all three?? Is there a better analogy to be drawn from the liability of master for slave in the Roman law of slavery, as Andrew Katz brilliantly suggsted at a GikII a while back??

In the short(er) term, though, the key problems may be around the more intangible but important issue of privacy. Robots are likely as with NAO above to be extensively used as aids to patients in hospitals, homes and care homes; this is already happening in Japan and S Korea and even from some conference papers I have heard in the US. Such robots are useful not just because they give care but because they can monitor, collect and pass on data. Is the patient staying in bed? Are they eating their food and taking their drugs and doing their exercises? Remote sensing by telemedicine is already here; robot aides take it one step further. All very useful but what happens to the right to refuse to do what you are told, with patients who are already of limited autonomy? Do we want children to be able to remotely surveille their aged parents 24/7 in nursing homes, rather than trek back to visit them, as we are anecdotally told already occurs in the likes of Japan?

There are real issues here about consent, and welfare vs autonomy which will need thrashed out. More worryingly still, information collected about patients could be directly channeled to drug or other companies - perhaps in return for a free robot. We already sell our own personal data to pay for web 2.0 services without thinking very hard about it - should we sell the data of our sick and vulnerable too??

Finally robots will be a hard problem for data protection. If robots collect and process personal data eg of patients, are they data controllers or processors? presumably the latter; in which case very few obligations pertain to them except concerning security. This framework may need sdjusting as the ability of the human "owner" to supervise what they do may be fragile, given leearning algorithms, bugs in software and changing environments.

What else do we need to be thinking about?? Comments please :-)

Sunday, August 08, 2010

Reforming privacy laws

[ORGCon] Reforming Privacy Laws from Open Rights Group on Vimeo.

Note that since this event in July the Commission has announced the draft reform proposal for the DPD will be delayed till probably the second half of 2011 (sigh!)

For those interested, the recent Wall Street Journal spread on privacy threats from a US perspective is also well worth perusing (follow links at end for related stories - there are 6 or so)The Sunday Times are supposed to be publishing a UK follow up today (August 8) in which Pangloss should be quoted - but since its behind paywall I haven't been able to check :-)

Wednesday, August 04, 2010

Google Makes TM Changes to Adwords Across EU

We defended our position in a series of court cases that eventually made their way up to the European Court of Justice, which earlier this year largely upheld our position. The ECJ ruled that Google has not infringed trade mark law by allowing advertisers to bid for keywords corresponding to third party trade marks. Additionally, the court ruled that advertisers can legitimately use a third party trademark as a keyword to trigger their ads

Today, we are announcing an important change to our advertising trademark policy. A company advertising on Google in Europe will now be able to select trademarked terms as keywords. If, for example, a user types in a trademark of a television manufacturer, he could now find relevant and helpful advertisements from resellers, review sites and second hand dealers as well as ads from other manufacturers.

This new policy goes into effect on September 14. It brings our policy in Europe into line with our policies in most countries across the world. Advertisers already have been able to use third party trademarked terms in the U.S. and Canada since 2004, in the UK and Ireland since 2008 and many other countries since May, 2009.

The most interesting bit for Pangloss is that what accompanies this is a new type of notice and takedown procedure.

In the affected European countries after September 14, 2010, trademark owners or their authorized agents will be able to complain about the selection of their trademark by a third party if they feel that it leads to a specific ad text which confuses users about the origin of the advertised goods and services. Google will then conduct a limited investigation and if we find that the ad text does confuse users as to the origin of the advertised goods and services, we will remove the ad. However, we will not prevent use of trademarks as keywords in the affected regions.

This is an interesting way of implementing the caveats in the ECJ decision. Google have generally sought to automate all their processes as far as possible, whereeas this will create a lot of manual work in processing what will no doubt be a storm of cease and desist notices - compare the Content ID approach on YouTube where take down exists and is faithfully followed, but there is also a push towards persuading IPholders to submit their own works for pre emptive filtering. However in this case they clearly think the work involved in implementing this new scheme will make more money for them in advertising revenue, than it will lose in costs of manual take down. And take down should fend off most future litigation, though not, I suspect, all. For businesses , a harmonised policy through all EU is always a boon.

It would be interesting to see some empirical data emerging on how this affects the choice of keywords, click-through and text of AdWords ads in future, and how this does or not benefit the public interest in access to information in advertising. Google's usual approach to open data should be helpful here. (Will takedown notices under this scheme go to Chilling Effects website, as linking-to-content take down requests do? I hope so.)

Thursday, July 22, 2010

We are not amused? Jokes, twitter and copyright

A. .. to steal someone else's joke posted on Twitter??

The Grauniad reports today on the latest spat in the turf war that is developing on Twitter between comedians trying out jokes and material, and passing other parties quietly re using thus material, sometimes explicitly under their own name.

It seems that Keith Chegwin, now no longer for some while the fresh faced lad of Saturday morning TV, has hit rock bottom and resorted to passing off jokes gathered on Twitter as his own "old" material.

Chegwin decided to use his account, where he has more than 36,000 followers (no, me neither), to broadcast a whole load of gags and one-liners. He claimed that these were either his own work, or traditional gags minted by long-dead comics.Unfortunately, they weren't. Among the gags retold by the one-time player of pop were identifiable jokes written by a number of contemporary standup stars, including Milton Jones, Lee Mack and Jimmy Carr. And what Cheggers presumably envisaged as a warm-hearted bit of fun has stirred up a sizeable amount of bad feeling within the comedy community. One comedian, Ed Byrne, even took Chegwin to task on Twitter, telling him he was wrong not to credit "working comics" for the jokes he was using.

This is not the first occasion of such, er, lack of amusement, emerging. My esteemed colleague @loveandgarbage tells me that this is a common source of disquiet. Comedians like to test and work on their material and Twitter with its potential for response and re-tweeting is a prfect venue for this. But the real question is, does anyone own a joke? Should they? Isn't this common cultural property? Where would society be if the first person to invent a "knock knock " job had asserted copyright in it?

Jokes - and especially tweeted jokes - are often quite short, vaguely familiar variations on a theme, and don't look much like the public conception of a "literary work", which is the applicable category of copyright (for written down jokes anyway). But the law as usual is not as simple as ordinary common sense.

Copyright exists only in works which are "original literary works". But case law has set a very low bar on such protection. A "literary" work has been held to include a long list of extremely unexciting written-down "things", eg, exam papers, football coupon forms, and a large number of meaningless five letter words used as codes. Looking at rather short literary works, it is generally acknowledged, eg, that some particularly pithy headlines might well engage copyright, though slogans are more contested, and usually protected by trade mark. There is the famous Exxon case, Exxon Corp. v. Exxon Insurance Consultants International Ltd [1982] Ch. 119, in which the English court held one word was too short to be a literary work. But 140 characters is somewhat longer and there is an interesting quote in the Exxon case from University of London Press Ltd. v University Tutorial Press Ltd. [1916] 2 Ch. 601 in which Peterson J. said, at pp. 609-610:

The objections with which I have dealt do not appear to me to have any substance, and, after all, there remains the rough practical test that what is worth copying is prima facie worth protecting.Copying jokes certainly seems to be a worthwhile economic activity. But are jokes "original"? There is surely an argument that, like recipes, every joke that exists has already been invented in some fundamental form - and therefore can be freely copied and adapted. Yet jobbing comedians do put a great deal of work into, and base their income on, inventing "new" jokes - and as the Grauniad note, the culture has shifted since the 80s to a point where comedians now regularly claim to "own" their jokes (I've also just been referred to this fascinating piece):

The idea that a comedian had outright ownership of his material seems to have taken root in this country once Manning et al gave way to the Ben Elton generation. For the original alternative comedians, simple gag-telling was far less important than presenting a fully-formed original perspective on the world. And if you were trying to offer an audience something distinctive (with all the added hard work that involves) then it became crucial to ensure that your gags were wholly your own....In recent years, the main victims of plagiarism in standup have been those comics who rely heavily on one-liners and quickfire jokes. For gag thieves, these present the perfect opportunistic crime: they're easy to lift and contain fewer hallmarks of the originator's personality.So maybe there is copyright in the jokes in question, and poor Cheggers is a copyright pirate. (Appealing to Technollama here to insert a Photoshop mock up pic!) But there is a serious point here, of which the Twitter joke is (paradoxically) a good example.

Is there copyright generally in any tweet? If so, what happens to re-tweeting? Passing around tweets by re-tweeting them is, for most tweeters, welcome : both providing an ego boost and allowing the community to share useful and amusing information at lightning speed. Yet if copyright exists in tweets, such activity is prima facie copyright infringing.

Again, there is a strong argument that by writing in an unprotected, open to the public, Twitter account, you are granting an implied license to copy. (Twitter itself seems to recognise this by providing no re-tweet button where the tweet is a friends-only one.) However the "implied license" argument has been frequently repelled on the Net generally: it is now very well accepted that simply posting something on a website, like a photo, or a story, does not in any way grant permission to all and large to reproduce it (cf a thousand spats over fans downloading pictures of their heroes from official media websites). Why should Twitter be any different? As usual, this would very much be on a case by case basis and depend on intentions, if litigation was ever to occur.

So we are left in a dilemma. If comedians are to get protection, we may prejudice perhaps the fundamental mechanism by which Twitter adds value to its community: the re-tweet.

But that's not the only problem. Presumptively granting copyright to tweets would allow particular tweets to be easily suppressed from distribution on threat of legal action, something that migt have serious chilling effects on freedom of speech.

Most recently, eg, take the Ben Goldacre/ Gillian McKeith spat, over whether Ms McKeith had called Mr Goldacre a liar on Twitter. Conveniently for the Goldacre side, someone had taken a screen cap of the incriminating tweets by McKeith, before she sensibly and fairly quickly deleted them. I wondered at the time if these tweets were not her copyright, and thus illicitly copied and distributed - as clearly she had not given permision, or if she had, had withdrawn it by deleting the tweets on her own account. And copyright can be so much easier a way to suppress speech than libel since it does not involve any enquiry over whether what was said was a lie or detrimental to anyone's reputation.

Of course, again (as with yesterday's FOI post) in copyright, there are exceptions for news reporting and public interest elements. But these are untested for social media and particularly for amateur tweeters rather than professional journalists. (It is interesting in the two pieces linked to above, that the Guardian themselves link directly to the screen-capped tweets, but Goldacre, a clever careful man, does not. :) Most lay people receiving a cease and desist on copyright grounds would probably delete a re-published tweet without demur. This could be the next way to suppress speech on a vigorous liberal forum like Twitter for everyone from Ms McKeith to the Church of Scientology.

Turning into a bit of a bad joke, eh? :-)

Tuesday, July 20, 2010

When does information not want to be free?

This is not, I imagine, the answer you, gentle reader, expected:)

Pangloss was recently asked by an acquantance, X, if he ran any legal risk by publishing on a website some emails he had obtained from the local council, as part of a local campaign against certain alleged illicit acts by that council. According to X, the emails could destroy the reputation of certain local councillors involved, and that they had had great difficulty extracting the emails, but finally succeeded. Obviously the value to the public in terms of access to the facts - surely the whole point of FOI legislation - would be massively enhanced if the obtained emails could be put on the campaign website.

My advice was that I was no FOI expert but since data cannot be released under FOI when it reates to a living person, DP and breach of confidence were not likely to be problems (though the latter was not impossible), and the main danger was surely libel, in which case truth was a complete defence. There would of course be a risk that councillor A might be lying about councillor B to the detriment of their reputation; in which case there was a danger of re publishing a libel. But that didn't seem all that germane and a public interest defence (though not one Pangloss would like to depend on, if it was her money) would certainly be possible.

I was wrong. Asking more people (and many thanks here to the wonderful ORG-legal list, especially Technollama, Victoria McEvedy, Simon Bradshaw, Daithi MacSithigh and Andrew Katz)) revealed the main weapon for gagging publication of FOI requests: that useful, all purpose, font of legal restraint - copyright.

In my innocence, I would have expected that a document obtained under FOI could be automatically republished by the recipient. Not so. The Office of Public Sector Information (OPSI)'s website reminds us that :

Information listed in Publication Schemes, which can be disclosed under FOI, will be subject to copyright protection. The supply of documents under FOI does not give the person who receives the information an automatic right to re-use the documents without obtaining the consent of the copyright holder. Permission to re-use copyright information is generally granted in the form of a licence.[italics added]As with most legal issues, the devil is in the detail here. Why should permission to republish only be "generally granted"? Why is it not compulsory to grant a license (though not necessarily for no consideration)? In the example at hand, the copyright holders have fought to prevent disclosure and have every reason to refuse to grant copyright permission. This seems both immoral and against the whole point of FOI.

Technollama advises me that where information is Crown copyright, there are indeed generally obligations under the Public Sector Information Directive (PSID) to release that information under some open licensing scheme. Currently this is Click-Use, but will soon be Creative Commons. An "open licensing" scheme does not necessarily mean you get to publish for free either, but it should mean copyright could not be used to gag publication. This all sounds good and right. The general reasoning behind the PSID obligations is that public money pays for public data, so the public should be able to access it and re-use it to create both economic and creative public benefits .

A similar reasoning lies behind the recent acclaimed open data.gov initiatives involving Tim Berners-Lee and Nigel Shadbolt's Web Science team. Various campaigns such as the Guardian's Free our Data calls have influenced UK public opinion to the point where the UK government seems to have acknowledged that public data should be able to be - well - published - and then re-used for public benefit.

However Crown copyright only applies in general to works generated by central not local government. And in any case it is more than possible that emails of this kind might be the copyright of the individual senders themselves, not the council, especially given the lack of a contract of employment.

(There are plenty of public bodies subject to FOI whose works are not Crown copyright, including eg the BBC and the ICO - see a selected OPSI list here - so this is going to be a common problem.) Of course it is possible the emails might not qualify for copyright at all - but given the low level of orginality test etc usually applied nowadays, this is pretty unlikely.

So here is a case where the law has already agreed that there is a public benefit in being able to scrutinise the activities of public officials (in this case, local councillors) yet there is no obligation to allow re-publication, merely a suggestion. In this case, the incentive to allow public republication is ethical and moral, not economic. Should that make any difference? I don't think so: perhaps the reverse.

Copyright of course has exceptions. Even if the council or councillors in question refused to license republication, it might be claimed that well known defences like news reporting or public interest might apply to allow copyright to be trumped. The OPSI site acknowledges this (see para 2). But we all know that the chilling effect of the threat of expensive litigation is likely to be an effective muzzle for most members of the lay public, if only vague and untested defences lie between them and big legal debts.

Would it not be far, far more sensible simply to require that where copyright materials are released under FOI (perhaps after a decent interval if necessary to allow for appeals) then a licesne to republish MUST be granted? Reasonable commercial conditions could apply depending on the value of licensing the information; which would be zero for scurrilous emails, but would stop people using FOI as a back door to getting free copies of expensive information. (Though as noted, the trend is for free release of public data anyway.)

The UK is not the only country to allow this under its FOI law In Canada, in 2008, Michael Geist discovered that the Vancouver BC government were asserting copyright over released by FOI materials. He wrote:

The notion that the media may not inform readers of harms to the public interest without first pleading for the state's permission and paying a copyright fee is deeply troubling.I could not agree more. The current situation is an appalling (and little known) travesty of what FOI is all about. It needs changed.

Thursday, June 24, 2010

gIKii Programme

Monday 28 June

09:30-5.30 Day One

9.30 Intro

9.45-11.15 Cloudy with a Chance of Legal Issues? Augmented and clouded platforms

- Andres Guadamuz, "We Can Tag It for You Wholesale: Augmented Reality and the User-Generated World".

- Martin Jones, "Human! We used to be exactly like them. Flawed. Weak. Organic. But we evolved to include the synthetic. Now we use both to attain perfection".

- Miranda Mowbray, "What the Moai know about Cloud Computing: Stone-age Polynesian technology and the hottest trend in computing today".

11.15 Coffee

11.30-13.15 We.Vote, You.Gov, She.Lurks? Social networks, politics, participation

- Lilian Edwards, "The Revolution will not be Televised: Online Elections and the Future of Democracy?"

- Judith Rauhofer, "The Rainbow Connection - of geeks, trolls and muppets".

- Caroline Wilson,"Is it Politic? Policy-makers' use of SNSs in policy-formation".

- Hugh Hancock, "Stories for Laws: the narratives behind the Digital Economy Bill, which ones worked, and most importantly: why?"

13.15-14.00 LUNCH

14.00-14.20 Apres lunch entertainment: Ray Corrigan - Maths for the Terrified (and lawyers)

14.20pm-15.40 Rip, mix, share, tweet?: Current IP/ Music Issues

- Dinusha Mendis, "If Music be the food of Twitter – then tweet on, tweet on . . . An evaluation of copyright issues on Twitter".

- Nicolas Jondet, "The French Copyright Authority (HADOPI), the graduated response and the disconnection of illegal file-sharers".

- Nicola Osborne, "Dammit! I'm a Tech (the "Services" or "Site") Punter (the "User" or "Member") not a Lawyer!"

-

Megan Carpenter, "Space Age Love Song: The Mix Tape in a Digital Universe".

15.40 Tea

16.00-17.30 pm Crime and Punishment Privacy

- Andrea Matwyshyn, "Authorized Access".

- Rowena Rodrigues, "Identity and Privacy: Sacred Spice and All that's Nice".

- Andrew Cormack, "When a PET is a Chameleon".

19:30 Sponsored conference diner.

The Apex City Hotel, 61 Grassmarket, EH1 2JF

Tuesday 29 June

9.30-11.00 Just Google It, Already!

- Daithi Macsithigh, "What We Talk About When We Talk About Google".

- Trevor Callghan, "GOOGLE WANT FREND!"

- Wiebke Abel, Burkhard Schafer and Radboud Winkels, "Watching Google Streets through a Scanner Darkly".

11.00 Coffee

11.15-13.00 Just Artistic Temperament? IP law and theory

- Steven Hetcher, "Conceptual Art, Found Art, Ephemeral Art, and Non-Art: Challenges to Copyright's Relevance".

- Chamu Kappuswamy, "Dancing on thin ice - Discussions on traditional cultural expression (TCE) at WIPO".

- Gaia Bernstein, "Disseminating Technologies".

- Chris Lever, "Netizen Kane: The Death of Journalism, Artificial Intelligence & Fair Use/Dealing".

13.00 Lunch

2.15-16.00 One World is Not Enough: law and the virtual / game

- Simon Bradshaw and Hugh Hancock, "Machinima: Game-Based Animation and the Law".

- Ren Reynolds (& Melissa de Zwart), "Duty to Play".

- Abbe Brown, "There is more than one world...."

- Michael Dizon, "Connecting Lessig's dots: The network is the law".

Huge news - You Tube wins on safe harbor vs Viacom

"

Today, the court granted our motion for summary judgment in Viacom’s lawsuit with YouTube. This means that the court has decided that YouTube is protected by the safe harbor of the Digital Millenium Copyright Act (DMCA) against claims of copyright infringement. The decision follows established judicial consensus that online services like YouTube are protected when they work cooperatively with copyright holders to help them manage their rights online.

This is an important victory not just for us, but also for the billions of people around the world who use the web to communicate and share experiences with each other. We’re excited about this decision and look forward to renewing our focus on supporting the incredible variety of ideas and expression that billions of people post and watch on YouTube every day around the world.

UPDATE: This decision also applies to other parties to the lawsuit, including the Premier League".

Commentary at TechDirt and hopefully, from me in next few days. This is big.

Thursday, June 17, 2010

A Day in Paris (Is Like a Year In Any Other Place.)

Danny Weitzner, who was a fresh faced freedom fighter for the CDT when I first met him, transmogrified into a rising star at the WWW and MIT, and is now an adviser to Obama (ah, why doesn’t UK academe provide this kind of career path!) lead the forces favouring, by and large, US-style industry self regulation, but noted that even in 1731, Benjamin Franklin had recognised need for intermediary immunities by presenting an “apology for printers” (of the human, not inkjet, kind) lest they be persuaded by criticism to print only texts they were personally convinced by.

Peter Fleischer, chief privacy counsel for Google, made the political decidedly personal, by commencing his intervention on privacy and intermediaries with anecdotes about being a convicted criminal who could no longer enter Italy (prompting mildly irascible responses from various Italians trying to make it plain they were not exactly the new China). Gary Davis from Ireland, perhaps a tad controversially for a data protection deputy commissioner, noted that there seemed to be emerging agreement on trading personal data for free web 2.0 services, but the question was, how much data was too much data; and Bruce Schneier (no link needed!) created the biggest stir of the day (to Pangloss’s silent cheers) by mentioning almost casually that, at least in relation to security, he had never had much time for user education. An unnamed EU Commission person made the sign of the cross and quoted liberally from the EC’s Safer Social Networking principles. Lightning did not however smite the infidel Schneier.

Jean Bergevin, in charge of the EC Commission’s much delayed but upcoming review of the E-Commerce Directive (ECD) (expect a consultation soon) took ferocious notes and reminded those present that although copyright and criminal liability may steal the headlines, the exclusion of gambling from the ECD gives a case study of how these things pan out (clue: not well) when safe harbours for intermediaries are not in place. The response seemed to be for the actual gambling hosting websites to move safely offshore, leading to undue pressure from states against payment intermediaries, so as to starve the unauthorised gambling sites of funds; yet, on the whole, these strategies merely multiplied bureaucracy and were still unsuccessful, since the grey market found ways round them (as it did, I noted, when similar strategies were applied to stimey offshore illegal music sites like AllofMP3.com in Russia). Later Mr Bergevin finally enlightened me as to why the ECD excludes data protection and privacy from its remit, as famously was publicised during the Google Italy case; not some abstract academic justification, but just that “that belonged to another Directive”. Time to raise the issue of intermediary liability in the ongoing DPD reform process then, methinks?

My own main contribution came in the first scene-setting session, where Prof. Mark MacCarthy of Georgetown University kicked off discussion on whether the OECD (which is also soon to review its longstanding and much applauded privacy guidelines) could conceivably come up with similar global guidelines on intermediary liability acceptable to all states, all types of intermediaries (ISPs, search engines, social networking sites, domestic hosts, user generated content sites?) and all types of content related liability (copyright, trademark, porn, libel, privacy, security??)? Everyone agreed that once upon a time a rough global consensus on limited liability, based around the notice and takedown (NTD) paradigm, had been achieved c 2000, with the standout exception of the US’s CDA s 230(c), which provided total immunity to service providers in relation to publication torts, but which was seen in the EU at least as something of a historical accident.

Since then, however, twin pressures from both IP rightsholders seeking solutions to piracy, and states keen to get ISPs to police the incoming vices of online child pornography, pro-terror material and malware, had converged to drive some legislatures, and some courts, towards re-imposing liability on online intermediaries (graduated response laws and ISPs being one of the most obvious case studies) and even moving tentatively from a post factum NTD paradigm to an ex ante filtering duty (SABAM, some Continental eBay counterfeit goods cases, the projected Australian mandatory filtering scheme for adult content). While the “top end” of the market might sort its own house out in the negotiable world of IP without further regulation (see the protracted Viacom v YouTube saga, which could be seen as a very expensive game of blind negotiator’s bluff) other areas were (still) less amenable to self regulation.

Privacy was identified very early on as an outstanding example of this: getting sites like Facebook and Google, which live off the profits of selling their client’s personal data, to take the main responsibility for policing those clients’ privacy was, as one speaker said, like getting the wolf to guard the sheep. Ari Schwartz of the CDT interestingly noted the new-ish difficulty of getting businesses like Facebook to take responsibility vis a vis their own users for third party apps using their platform. Apple however were piloting a new model of responsibility by careful selection of apps allowed to use their platforms, while Google Android were doing it differently again (I want to come back to this fascinating discussion in a separate post).

My own points circled around the idea that increasingly, the current idea of “one size fits all” enshrined in the ECD does not really work; more in relation to types of liability though (copyright vs libel , for example, with very diifferent balances of rights and public policy at work) than in relation to types of intermediaries (did search engines really need a special regime, of the kind the DMCA has and the ECD doesn’t, I was asked? My answer, given the fact that the two most troublesome EC Google cases – Italy and Adwords – have actually related to hosting not linking – was probably no (though that still leaves Copiepresse to sort out).)

However there was also room for thinking about different regimes for different sizes of intermediaries – small ISPs and hosts, eg, will simply crumble under the weight of any potential monitoring obligations, jeopardising both freedom of expression and innovation, while in a similar bind, Google can afford to build a Content ID system for YouTube which lets filtering become, effectively, a monetising opportunity. All this of course still avoided the main problem, of how complicit or “non neutral” (in the words of the ECJ Adwords case) an intermediary has to be in relation to illegal or infringing behaviour or content (cf eBay, YouTube, Google etc) before it should lose any special immunities. On that point, even the EU let alone the OECD is going to have to work very, very hard to find consensus.